The

Raspberry Pi model 3B astonished me today.

Below I'll talk about my intentions for this device, namely off-grid automation at my family's beach house. Here above the fold I want to discuss r-Pi as a desktop alternative.

Fedora 29, the latest version of the Linux distribution I've been using forever on my workstation and laptop, was released yesterday. Just for the hell of it I installed it on my r-Pi and I'm blown away by how well it performs. Not well enough to replace my workstation but not far off.

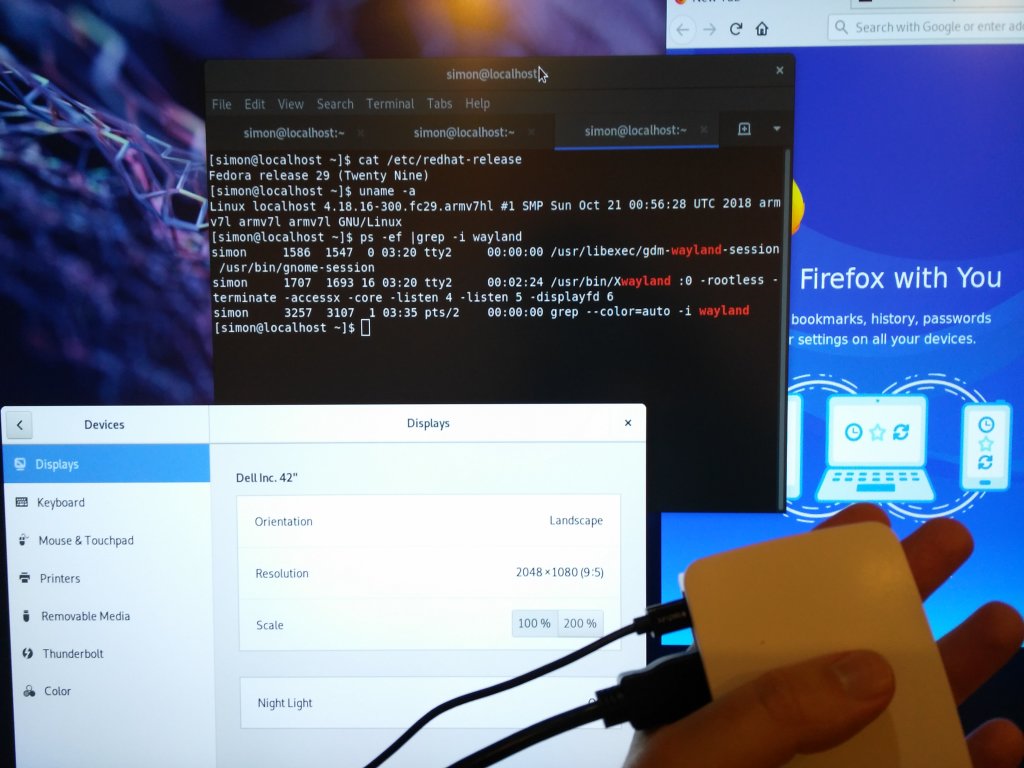

In this photograph the $NZ89 device I'm holding in my hand is running

Fedora full noise with

GNOME 3.30 on

XWayland.

Okay it's only driving my 3840x2160 monitor at 2048x1080 but it's doing that without dedicated graphics hardware. Trust me when I say, that is impressive: this is the

no compromises heavy duty Linux user interface configuration for a power user and r-Pi is keeping up.

Here's the thing: I can outsource storage and processing. As soon as r-Pi can give me a snappy user interface that drives my monitor at full resolution and can run a Windows VM to host those annoyingly proprietary applications I need to do my job, it can replace my workstation. After playing with Fedora 29 on Raspberry Pi 3B today, I expect the next hardware release to be on the cusp.

Now to the interesting part, Raspberry Pi for living off-grid or,

Simon's Cunning Plan to Survive the Zombie Apocalypse.Here's the

situation: our family beach house is the perfect place to survive the zombie apocalypse. It's located in a sheltered bay on a remote island in the

Marlborough Sounds accessible only by boat or by helicopter. It has a constant fresh water supply, an abundance of protein from sea life and wild mammals, carbohydrates and nutrients from fruit trees, nut trees, and vegetable cultivation.

From the perspective of

Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs quite a few people could survive there comfortably as enlightened hunter/gatherers.

The primary

constraint is that it's mostly uninhabited: it's a holiday home sitting idle for most of the year. Which means it needs to operate fairly autonomously, at least until the fall of civilisation when I arrive to rule the post-apocalypse as a not-very benevolent autocrat.

Which is where Raspberry Pi comes in, bringing me to our

use case: operating the place autonomously whilst it's unoccupied, and facilitating operations when it is.

Which brings me to

requirements. The beach house comprises the following systems:

- Energy System

Solar and Wind turbine collection, battery storage, 240v distribution.

- Heating System

LPG Califont

- Water System

Riparian collection, tank storage

- Sewerage/Fertilisation System

Biological waste management reliant upon electricity for aeration and pump.

- Telecommunications System

24 dBi antenna and amp tuned by hand to attain one bar of cellular signal after many angry hours if I'm lucky.

- Security system

Motion detection sensors and cameras.

- Environment

Barometric pressure, outdoor temperature, indoor temperature, wind direction, precipitation, &c.

- Irrigation

Not required. In New Zealand stuff just grows.

Which brings me to

current state. Right now the beach house is serviced by a

Raspberry Pi Model 2B running

Open Energy Monitor and

OpenHab. Currently this monitors/manages the energy system and provides a user interface, and a framework for integrating the other systems.

Which brings me to

future state. Managing the Heating, Water, Sewerage and Environment systems requires

mechanical devices with digital interfaces:

IoT sensors to turn valves on and off, measure levels and flows, record environment values and so on. Which is where this daughterboard comes in.

This is the

Dragino LoRa GPS HAT for r-Pi providing

GPS and establishing a

LoRa network for the sensors required to manage the non-digital systems. It cost me $NZ60.

When I get around to drawing it I'll add a diagram to this post to illustrate what all of this looks like conceptually.

In the meantime and to summarise, the Raspberry Pi does everything I need for a paltry $NZ120 or so, and over the next few years I'll introduce sensors to integrate the other systems one by one at very minimal cost.

And I'll very much enjoy doing it. When you're in the Marlborough Sounds catching your daily limit in fifteen minutes because the fish are jumping on the hook like they've joined a cult and the highlight of your week is a visit from the mailboat, whiling away the time on IoT automation is quite the pleasure.

-SRA. Auckland, 3/xi 2018.